Is the First Brands Collapse a Warning Sign?

In early October 2025, the private credit sector was rocked by the sudden collapse of First Brands Group, a major US auto parts supplier. With over $11 billion in declared liabilities and allegations of $2.3 billion in hidden debts through opaque off-balance-sheet arrangements like receivables factoring and inventory reverse-factoring, the bankruptcy sent shockwaves through financial markets. Creditors such as Jefferies, UBS, and BlackRock faced hundreds of millions in potential losses, while trade finance firm Raistone, reliant on First Brands for 80% of its revenue, initiated legal proceedings and slashed its workforce by half. Loans traded as low as 36 cents on the dollar, exposing the fragility of a sector that has ballooned to trillions in assets with minimal oversight.

This event isn’t isolated. It echoes a broader pattern of distress in private credit and trade finance throughout 2025, including the collapses of Stenn and Kimura in January, Rasmala Trade Finance Fund in May, and similar insolvencies at Tricolor and Artis Group. These cases highlight systemic issues: weak risk controls, misrepresented assets, and a reliance on non-bank lending that sustains “zombie companies”—firms barely servicing debt through endless borrowing. Regulators worldwide, from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission to US authorities, have warned of rising default rates and potential investor losses in this rapidly expanding market.

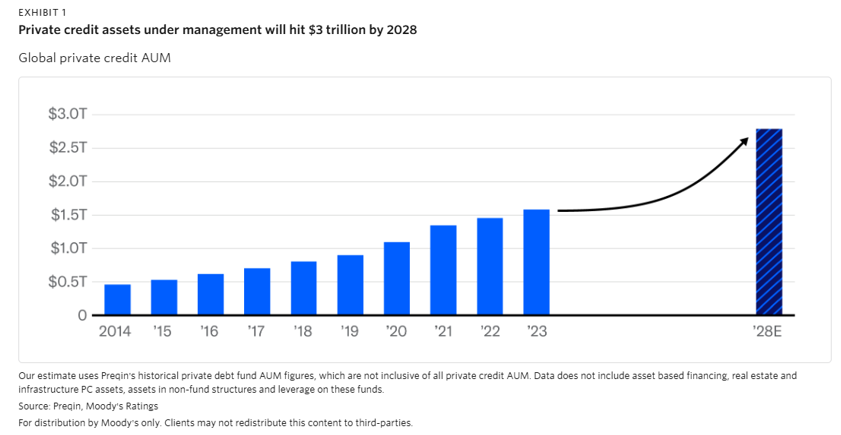

At the heart of this turmoil is an investment thesis gaining traction among analysts: private credit is essentially mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDO) in a new wrapper. Unlike the 2008 crisis, where these toxic assets were bundled and hidden on bank balance sheets, today’s risks lurk in private credit funds—shadow banking entities that operate with even less transparency and regulatory scrutiny. Private credit, which involves non-bank lenders providing direct loans to companies often too risky for traditional banks, has grown explosively to an estimated $2 trillion globally, supporting vulnerable businesses amid rising interest rates.

Growing Private Credit Market

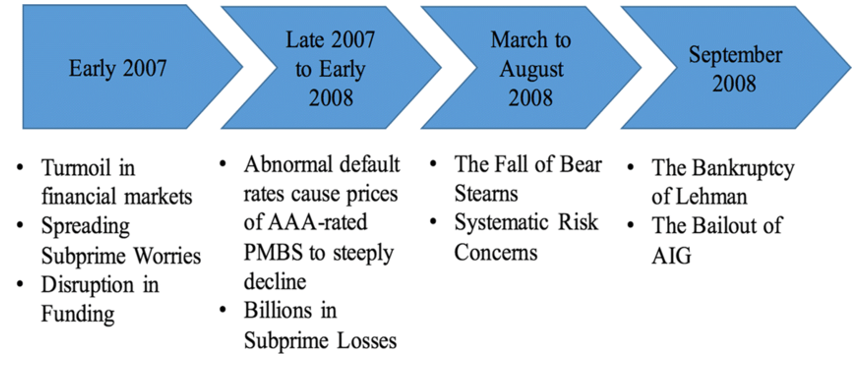

The parallels to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 are striking. Back then, subprime mortgages—loans to high-risk borrowers—were packaged into MBS and CDOs, rated as safe investments despite underlying flaws like inflated asset valuations and predatory lending. When housing prices peaked in 2006 and delinquencies surged, the opacity of these instruments triggered a cascade: hedge funds collapsed in 2007, Bear Stearns was acquired in March 2008, Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in September 2008 with $600 billion in losses, and AIG required an $85 billion bailout. Global equity markets plummeted, with the S&P 500 falling 57% from its October 2007 peak to March 2009 trough, the FTSE 100 dropping 48%, and the MSCI World index shedding 59%. Over 5 million Americans lost homes to foreclosure, and the crisis forced $700 billion in TARP bailouts.

Timeline of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis

Today, private credit mirrors this setup. Loans to subprime borrowers, often in sectors like auto financing or leveraged buyouts, are bundled into funds sold to investors seeking higher yields. But without public disclosure or stringent banking regulations, risks like overleveraged borrowers and double-pledged assets remain hidden until defaults erupt. The First Brands case exemplifies this: the company pledged the same invoices to multiple lenders, concealing debt much like how subprime loans were misrepresented in CDOs. Similarly, Tricolor’s collapse involved undisclosed debts in subprime auto loans, drawing direct comparisons to 2008’s mortgage meltdown.

Experts have long warned of these similarities. A J.P. Morgan analysis draws parallels to the subprime crisis, noting mounting losses in private credit amid rapid growth. The World Financial Review calls private credit “Wall Street’s next crisis,” highlighting risks akin to pre-2008 subprime markets, such as questionable valuations and unsecured exposures. An IMF report urges closer monitoring of the $2 trillion market, citing vulnerabilities in shadow banking that could amplify shocks. Hausfeld’s perspectives blog points to the sector’s opacity and illiquidity, reminiscent of the subprime buildup.

Recent X discussions amplify these concerns. Investor Matein Khalid, in posts from October 3 and 11, 2025, likens the First Brands and Tricolor failures to the 2008 subprime daisy chain, predicting a $3 trillion consumer credit meltdown that could freeze funding markets, bust stock bubbles, and collapse oil prices—much like Brent’s drop from $148 to $35 in 2008. He warns of contagion to property markets, including Dubai’s, and notes plunging shares in private equity giants like Blackstone (from 189 to 160) and Citigroup (from 104 to 97). Other users echo this: QE Infinity sees First Brands as the spark for a credit cycle bust, potentially freezing markets and causing financial crises. Jeffrey P. Snider highlights auto industry breakdowns as a canary for broader economic deflation and financing woes. Pablo Gil notes alarms on Wall Street from Tricolor and First Brands, fearing opacity could hide latent risks like in 2008.

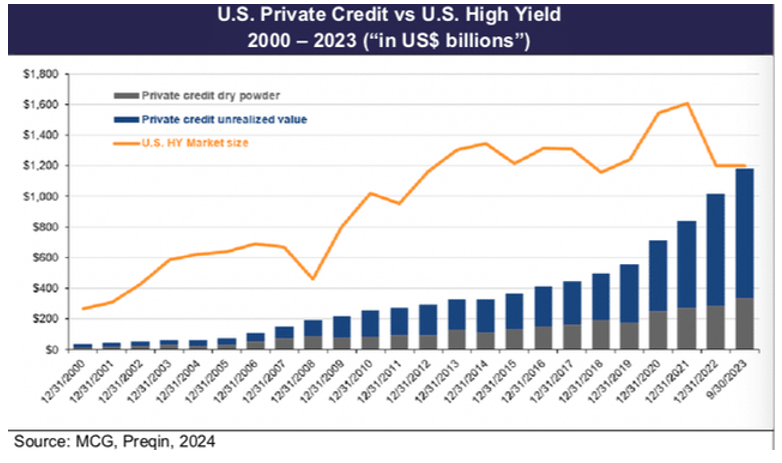

Private Credit vs. High Yield Market Size Comparison

The key difference—and danger—is placement. In 2008, risks were in regulated banks, allowing central bank interventions. Now, they’re in private funds held by pensions, insurers, and retail investors, with no lender of last resort. This democratizes risk but heightens contagion potential, as losses could erode retirement savings and trigger runs on funds.

Should we be worried? Absolutely, but with nuance. The First Brands collapse is a glaring warning sign of embedded risks in private credit, potentially heralding a 2008-style crisis if defaults cascade amid stagflation and deflation in major economies. However, post-GFC reforms have strengthened banks, and private credit’s fragmentation might limit systemic spread—if transparency improves. Regulators must demand better oversight, risk premiums, and disclosures to avert disaster. Investors should diversify away from illiquid assets and monitor indicators like CLO issuance and credit spreads. History rhymes; ignoring this echo could prove costly

THE TOP PICK OF LAST MONTHS WEBINAR IS +96% IN JUST 4 WEEKS!

DONT MISS OUT

GENERAL ADVICE WARNING:

Recommendations and reports managed and presented by MPC Markets Pty Ltd (ABN 33 668 234 562), as a Corporate Authorised Representative of LeMessurier Securities Pty Ltd (ABN 43 111 931 849) (LemSec), holder of Australian Financial Services Licence No. 296877, offers insights and analyses formulated in good faith and

Opinions and recommendations made by MPC Markets are GENERAL ADVICE ONLY and DO NOT TAKE INTO ACCOUNT YOUR PERSONAL CIRCUMSTANCES, always consult a financial professional before making any decisions.